Introduction

The Lamiaceae family is of great diversity and variety, with a cosmopolitan distribution. It is comprised of about 7200 species organized into 236 genera, which includes plants, herbs, shrubs and trees.1,2 Plants in this family are characterized by verticillaster inflorescence, two-lipped open-mouthed tubular corolla, opposite decussate leaves, quadrangular stem, etc.1,2 Most of the species are aromatic and possess essential oils. Many members of the Lamiaceae family are widely cultivated for their aromatic qualities and for medicinal properties. The plants of this family are easy to grow and can be easily propagated. Species of this family are grown for their edible leaves, as decorative (e.g. Coleus), as edible seeds (e.g. Salvia hispanica: Chia seeds), apart from their culinary and medicinal applications (e.g. Ocimum spp.).

Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.), is one of the multipurpose aromatic perennial herb of the Lamiaceae family which is commonly known as Badri tulsi, Vantulsi, Sathra, Jakhambooti, Baslooghas, and Jonk-Jari in India. Centre for origin of Origanum is hills in Western Asia and the Mediterranean region, but it has now naturalised in some areas of Mexico and the United States.3 O. vulgare is cultivated in sub- and temperate regions of India, particularly in the Himalayan area.4,5 It is one of the most traded culinary herbs in the world.6,7

Plants are generally perennial herb and reach up to 80 cm height and have ovate leaves, white or purple flowers and terminal corymbose cyme. The plants are also characterized with gynodioecious and male sterility conditions. The essential oil of Oregano is composed of carvacrol and/or thymol as dominant components, followed by γ-terpenine, p-cymene, linalool, terpenine 4-ol, and sabinene hydrate. The oil is known to possess anti-bacterial, anti-viral, anti-septic, anti-microbial, anti-oxidant, anti-fungal, anti-coagulant and energetic action and flavouring properties.5,9 Many studies have reported intra-species variations in morphology, anatomy, volatile composition chemotypic, pharmacogonostical values and geographical variations in O. vulgare, O. vulgare ssp. vulgare and O. vulgare ssp. hirtum (Link).4,7-23 In this review article, we shed light on the origin, distribution, botanical description, cytological and breeding studies, phytoconstituents and biological activities, cultivation practices and its therapeutic studies of O. vulgare.

Classification

Kingdom: Plantae

Class: Magnoliopsida

Order: Lamiales

Family: Lamiaceae

Genus: Origanum

Species: vulgare

Figure

|

Figure 1: A plant of Origanum vulgare L. |

Origin and Geographical distribution

Mediterranean, Euro-Siberian and Irano-Siberian regions are centre for diversity of the genus Origanum. About 75% of the Origanum species are concentrated in the East Mediterranean sub region.24 Presently, it’s found throughout Central Europe, North America and in some countries of Asia Minor. In India, the plant is generally found in the temperate Himalaya between 1,500 and 3,600 m high from Kashmir to Sikkim. O. vulgare was discovered in seven districts of Uttarakhand including Nainital (1480-2240 m), Uttarkashi (2500-2800 m), Rudraprayag (3555 m), Chamoli (3260 m), Bageshwar (2260 m), Champawat (1840 m) and Almora (2220 m), all of which are located at various altitudes.

Botanical discription

Origanum is one of the genera represented by 10 sections with 43 species, 6 subspecies, 3 botanical varieties and 18 naturally occurring hybrids.24 It is an aromatic, branched, perennial herb and average plant height of 30-80cm has been reported by many researchers.25,26 Weglarz et al. (2020) studied the differences between Greek oregano, O. vulgare L. subsp. hirtum (Link) Letswaart, and common Oregano, O. vulgare L. subsp. vulgare, in central Europe, and reported that the plant height in common Oregano was 36.11 ± 1.93 cm while in Greek Oregano, it was 26.15 ± 1.86 cm. Greek Oregano plants grown in Poland were about 10 cm lower than common Oregano plants.27 For instance, common Oregano plant’s height ranged from 18 to 59 cm while in Greek Oregano, it vared from 67.8 to 79.9 cm. Leaves are broadly ovate, 10-44 mm long and 5-25 mm wide with opposite phyllotaxy and the number of primary branches ranged from 5 to 55.22

The flowers grow in terminal corymbose cyme. Flowers are pale, white or pink in colour and 5-8 mm long. The calyx has five sepals and four stamens. The nutlets are brown in colour.4,28-32 Dorsiventral leaves have diacytic type of stomata. Trichomes are simple or covering type and glandular type. The peltate trichomes consists of enlarged secretory head, made up of 12–16 glandulous cells covered by a common cuticle. Volatile oils are released upon rupture of the cuticle, which are responsible for synthesis of other more hydrophilic metabolites like phenolic compounds and polysaccharides.27,33,34 The upper and lower epidermal cells were found to be wavy with thin cell wall. Vascular bundle is restricted to the midrib region and comprises of collateral arrangement of xylem and phloem in stem.22

The variation in O. vulgare L. populations in terms of morphological, anatomical, histo-chemical, germination and essential oil composition was primarily restricted to European nations, whereas such studies from India are limited.22,23,24,35-38

Cytological and Breeding Studies

Most of the Oregano spp. consists of 2n=30 chromosome number and the basic number of chromosome are x = 15.23,39 In Origanum species, controlled hybridization using the flower emasculation technique is very expensive due to small size of the flowers and the type of inflorescence.40 The well-known dioeciousness in Origanum genus can provide us with tools to control crossing.41 Male sterility is well-studied in O. vulgare subsp. vulgare and it has a complex genetic background.42,43 This male sterility can be used in heterozygous breeding for higher dry matter production and improved homoplasmy dominance, or in interspecific crosses to combine desirable traits from different species. For genetic improvement, high variability is found in Origanum population which can be good source for selection work.44-47 Conventional and molecular breeding can be used for enhancing essential oil content and its most distinctive chemical compounds.48-50 Recent findings revealed that Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD), Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) and Selectively Amplified Microsatellite Polymorphic Loci (SAMPL) markers were effective instruments for identifying the genetic makeup of O. vulgare taxa.51, 52-63

Essential oil and its chemical composition

Plants of the family Lamiaceae comprise a rich storehouse of phytochemical and biochemical such as flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and terpenoids etc. which can be oppressed for its antimicrobial activities, antioxidant activities, food preservatives, insect repellants and other therapeutic properties.22

The essential oil of Oregano contains carvacrol and/or thymol as the main component(s) and other minor constituents such as c-terpinene, p-cymene, linalool, terpinen-4-ol, and sabinene hydrate. Carvacrol is an important impact compound of Oregano aroma and the largest component of the active extract of the aroma.64,65 Thymol and carvacrol are biosynthesized by aromatization of c-terpenine to p-cymene followed by hydroxylation of p-cymene.66

The yield of essential oil was affected by various factors which include geographical variation, genetic variation, seasonal and maturity variation, growth stages, part of plant utilized and postharvest drying and storage.67-74 During the flowering period, the essential oil content is at its highest level.75

Different studies reported different percentages of the compounds of the essential oil. Kokkini et al.( 2004) analyzed samples from six different locations in Greece and found that carvacrol amounts ranged from 1.7 to 69.6% and thymol ranged from 0.2 to 42.8%.76 The phytochemical screening by Prieto et al. (2007) disclosed 41 compounds in the essential oil contributing to about 99.6% to the total oil and the percentage of the dominant compounds viz. carvacrol and thymol was 54.7% and 22.1%, respectively.77 Studies conducted by Dimitrijevic et al. (2007) revealed that the amount of carvacrol was 33.51% and thymol to be 5.67% in the O. vulgare essential oil.78 Pande et al. (2012) collected different samples of O. vulgare from Kumauon region of Uttarakhand and their study revealed that the percentage of main compounds as Thymol (29.70 to 35.10%), Carvacrol (12.40 to 20.00%), y-terpinine (12.37 to 14.00% and p-cymene (6.69% to 9.80%).19 Similarly, Verma et al. (2012) studied the essential oil composition of O. vulgare and they reported that major components of oils were thymol (40.9-63.4%), p-cymene, (5.1-25.9%), γ– terpinene (1.4-20.1%), bicyclogermacrene (0.2-6.1%), terpinen4-ol (3.5-5.9%), α-pinene (1.6-3.1%), 1-octen-3-ol (1.4-2.7%), α-terpinene (1.0-2.2%), carvacrol (<0.1-2.1%). β-caryophyllene (0.5-2.0%) and β-myrcene (1.2-1.9%). Thymol, terpinen-4-ol, 3- octanol, α-pinene, β-pinene, 1,8-cineole, α-cubebene and (E)-β ocimene were observed to be higher during full flowering season.16

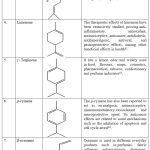

|

Table 1: Structure of chemical constituents found in O. vulgare and its biological activities. |

Biological activities

The fresh leaves and dried herb of oregano contains many biological activities which are as follows:

Antioxidant activity

O. vulgare‘s essential oil and plant product both have antioxidant properties. Several scientist demonstrated potent DPPH scavenging, protective actions against lipid peroxidation in liposomes, and activities to neutralise NO and H2O2.89-92

Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Due to the presence of carvacrol, Origanum essential oil has anti-inflammatory effects by preventing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and repressing the expression of inflammatory genes.93

Antimicrobial activity

O. vulgare extracts with phenolcarboxylic acids (cinnamic, caffeic, p-hydroxybenzoic, syringic, protocatechuic, and vanillic acid) as presumably active ingredients were found to have antimicrobial activity. Additionally, oregano essential oils’ fumigant toxicity for storage insects has been proven.94 The essential oil of Origanum have high biological and antimicrobial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, Klebsiella pneumonia, Bacillus subtilis, Streptomyces candidus and Candida albican.22 O. vulgare essential oil demonstrated antibacterial effects against Helicobacter pylori, which is associated with ulcers, Enterobacter cloacae, Micrococcus flavus, Proteus mirabilis, Salmonella enteritidis, S.epidermidis, and S. typhimurium.10 The essential oil of O. vulgare showed antifungal effects against Aspergillus flavus, A. parasiticus, A. fumigatus, A. terreus and A. Ochraceus.101-103

Antitumoral Activity

Tuncer et al. (2013) showed that O. vulgare L. has antitumor activity against breast cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo.95

Antihyperlipidemic activity

O. morjorana and O. vulgare leaf preparations in volatile oil, methanol, and water reduced elevated triglyceride and cholesterol levels in streptozotocin containing diabetic rabbits.52 O. vulgare aqueous extracts also demonstrated analgesic action.96

Anti-obesity Activity

Methanol extract of O. vulgare inhibits pancreas lipase.97 Pancrelipase is an important enzyme in the breakdown of triglycerides. Modifying lipid metabolism by preventing dietary fat uptake is one method for preventing or treating obesity.

Anti-hyperglycaemic Potentials

Essential oil, methanol, and water extracts of O. vulgare leaves substantially lowered blood glucose levels indicating that these extract are effective without affecting insulin secretion in diabetic rats.98

Hepatoprotective Activity

Aqueous extract of O. vulgare leaves has been shown to have hepatoprotective activity on CCl4-induced liver damage.99-100

Antiurolithic Activity

A crude aqueous methanolic extract of O. vulgare was reported to have anti-urolithic activity in addition to reducing the amount of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals produced in metastable calcium oxalate solutions. It also prevented and reversed toxic changes like weight loss, polyuria, crystal Luria, oxaluria, elevated serum urea and creatinine levels, and crystal deposition in the kidney compared to their respective controls.105

Antimelanogenic Properties

Rosmarinic acid methyl ester, which was isolated from O. vulgare had the capacity to lower the levels of melanin, tyrosinase, and DOPA oxidase in B16 cells. This research found that the isolated compound has anti-inflammatory and depigmenting properties that may be helpful as food additives and for the regulation of skin pigmentation.106

Effects on Human Sperm Mobility

Mbaye et al. (2019) examined the effects of Oregano essential oil (obtained from Fes, Morocco) on the viability and motility of sperm. Sperm vitality was determined by eosin 2% staining and examined under an optical microscope. Sperm movement was determined using a computer-assisted sperm analysis.107 This study emphasied that application of oregano oil has shown increased biological potential with best progressive sperm mobility and vitality.

Antiplatelet Activity

O. vulgare essential oil exhibited antiplatelet activity by preventing clot regression in plasma from Guinea pig and rat models. Phenylpropanoids were found to have a substantial correlation with antiplatelet potency, indicating a crucial function for this moiety in the suppression of clot formation.108

Other activities

Chopped oregano leaves and stalks could be used to control weeds in fields and pots due to presence of aroma-impact compounds like eucalyptol, borneol, b-bisabolene, and other minor constituents.109,110 Oregano essential oil had an anticoccidial influence on broiler chickens, while oregano herbal extract had a positive impact on rabbits’ resistance and production.111 According to studies conducted by Hussain et al. (2011), oregano essential oil has antimalarial properties and was efficacious against Trypanosoma cruzi.112-115

Therapeutic uses

Origanum vulgare L. has traditionally been used to treat gastrointestinal disorders, urinary tract disorders, dermatological affections, and disorders of the respiratory tract, including cough and bronchial catarrh (as expectorants and spasmolytic agents), as well as disorders of the urinary tract (as a diuretic and antiseptic).116 According to the National Library of Medicine, oregano products are taken orally for conditions such as allergies, headaches, painful menstrual cramps, urinary tract infections, and psoriasis. Oregano oil is also applied topically for conditions such as acne, dandruff, warts, wounds, muscle and joint pain, varicose veins and psoriasis.

Cultivation of Origanum vulgare

Oregano grows in regions with medium fertile soils, high elevations, and cool summers and is tolerant of cold and dryness. For oregano cultivation, light, well-drained loam is best. Compost is not required for growth because it thrives in soil that is only relatively fertile. The optimum oil pH for its growth ranges from 6.5 to 7.0. Suitable growing region with 5-28 °C, with 0.4-2.7 m of water per year.22 There is an effect of temperature on the qualitative and quantitative parameters of essential oil. According to Karamanos et al. (2013), levels of other compounds in essential oil are higher in cooler seasons, while carvacrol concentration is higher in warmer seasons (70.75-84.88%) in both leaves and inflorescences.117

Sowing time and methods of sowing

The Oregano germplasm (seeds) are planted in poly houses or green houses in the months of October and November in low altitude regions and in March and April in high altitude regions. In poly bags (12 × 9 inch and 150 gauge), 50 to 100 seeds, 20 to 30 recently sprouted soft or semi-wood cuttings (5-8 cm long aerial parts), or 5 to 10 perennial sprouted roots pieces (3 to 5 cm) could be directly sown. In the months of March and April, nursery growth is accomplished through stem cutting and sprouted root divisions22. After the development of nursery in poly house or greenhouse, the seedlings/ saplings of Oregano are transplanted on raised beds of nursery in the month of March and April.

Optimum spacing for plantation

Spacing of seedlings vary from 40, 50 and 60 cm in row to row and plant to plant spacing vary from 20, 30 and 40 cm . It has been reported by Ojha et al. in 2014 that plant biomass and plant weight has been increased by using 50 to 60 cm distance between rows and 25-30 cm within row respectively.22

Manure and fertilizers

Generally Origano plants do not require application of fertilizers for growth and development. Whereas studies conducted by Dordas et al. (2009) revealed that nitrogen is crucial for improving dry matter yields without significantly changing the essential oil content.118 Ojha et al. (2014) reported that application of farmyard manure at the rate of 20 t/ha was sufficient for proper growth of plant while treatment with 20:40:40: Kg N:P:K per hectare was correlated with high yield.22

Water and Weed management

For the proper growth of crop, the area should be effectively irrigated at the time of nursery establishment to maintain moisture.22 Watering should be done every 24 to 48 h when propagating through stem or root cuttings. A week’s worth of watering was needed during the field transplanting process. 3–4 times per month in the summer and 2–3 times per month in the cold. Weeds should be carefully removed from the beds.22

Harvesting and Post harvest management

To ascertain the economic yield of the plants, aerial parts are manually harvested two to three times. Aerial parts are harvested at various times and dried in shade and moderate heat to preserve their original colour and fragrance. Fully dried leaves and flowering spikes are stored and maintained in gunny bags and airtight bags. According to Chauhan et al. (2013), harvesting herbage at the full bloom stage had marginally better parameters than harvesting it at the early and late vegetative, flower initiation, and fruit set phases.119

Conclusion and Future prospective

The present review highlighted the classification, geographical distribution, botanical description, cytological and breeding aspects, chemical constituents, cultivation practices and various biological potential of Origanum vulgare.

Acknowledgment

Authors are grateful to Prof. (Dr.) Arun Kumar Dean, School of Basic and Applied Sciences, Shri Guru Ram Rai University, Patel Nagar, Dehradun for his kind support and suggestions.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Harley R. M., Atkins S., Budantsev A. L., Cantino P. D., Conn B. J., Grayer R., Harley M. M., Dekok R. P. J., Kreatovskaja T., Morales R., Paton A. J., Ryding O. and Upson, T. Labiatae. In: Kubitzki, K. (Ed.), The Families Genera Vascular Plants. 2004;6: 167-275.

CrossRef - Raymond M. H., Sandy A., Andrey L. B., Philip D. C., Barry J. C., Renee J. G., Madeline M. H., Rogier P. J., Tatyana V. K., RamonM., Alan J. P. and Olof Labiatea. In: Klaus, K. (Ed.), The Families Genera Vascular Plants. Vol. VII, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 2004.

- Arabaci T., Çelenk S., Ozcan T., Martin E., Yazici T., Açar , Uzel D., Dirmenci T. Homoploid hybrids of Origanum (Lamiaceae) in Turkey: Morphological and molecular evidence for a new hybrid. Plant Biol. 2020; 1-13.

CrossRef - Gaur R. D. Flora of the District Garhwal North western Himalaya (with ehtnobotanical notes). Transmedia, Srinagar Garhwal, India. 1999.

- Chauhan R. S. and Nautiyal M. C. Seed germination and seed storage behavior of Nardostachys jatamansi, an endangered medicinal herb of high altitude Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 2007; 92(11): 1620-1624.

- Chalchat J. C. and Pasquier B. Morphological and chemical studies of Origanum clones: Origanum vulgare ssp. vulgare. Essen. Oil Res. 1998; 10: 119-125.

CrossRef - D’Antuono L. F., Galleti G. C., Bocchini P. Variability of essential oil content and composition of Origanum vulgare populations from a North Mediterranean area (Liguria Region, Northern Italy). Annals of Botany. 2000; 86: 471-478.

CrossRef - Mockute D., Bernotiene G. and Judpentiene A. Chemical composition of essential oils of Origanum vulgare growing in Lithuania. Biologija. 2004; 4: 44-49.

- Wogiatzi E., Gougoulias N., Papachatzis A., Vagelas I., Chouliaras N. Chemical composition and antimicrobial effects of Greek Origanum species essential oil. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 2009; 23 (3):1322-4.

CrossRef - Andi S. A., Nazeri V., Zamani Z. and Hadian J. Morphological diversity of wild Origanum vulgare (Lamiaceae) in Iran. Iran. J. Bot. 2011; 17(1): 88-97.

- Kaul V. K., Singh B. and Sood R. P. Essential oil of Origanum vulgare from north India. J. Essen. Oil Res. 1996; 8: 101-103.

CrossRef - Pande C. and Mathela C. S. Essential oil composition of Origanum vulgare ssp. vulgare from the Kumaon Himalayas. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2000;12: 441-442.

CrossRef - Kumar N., Shukla R., Yadav A. and Bagchi, G. D. Essential oil constituents of Origanum vulgare collected from a high altitude of Himachal Pradesh. Indian Perfum. 2007; 51: 31-33.

- Bisht D., Chanotiya C. S., Rana M. and Semwal M. Variability in essential oil and bioactive chiral monoterpenoid compositions of Indian oregano (Origanum vulgare) populations from northwestern Himalaya and their chemotaxonomy. Industrial Crops Product. 2009; 30:422-426.

CrossRef - Prathyusha P., Subramanian M.S., Nisha M. C., Santhanakrishnan R. and Seena M. S. Pharmacognostical and phytochemical studies on Origanum vulgare (Laminaceae). Anc. Sci. life. 2009; 29(2): 17-23.

- Verma R. S., Rahman L., Verma R. K., Chnotiya C. S., Chauhan A., Yadav A., Yadav A. K. and Singh, A. Changes in the essential oil content and composition of Origanum vulgare during annual growth from Kumaon Himalaya. Curr. Sci. 2010; 98 (8): 1010-1012.

- Raina P. A., Negi K. S., Mishra K. S., Koranga S. S. and Ojha S. N. Chemical characterization of aromatic plants from Central Himalayas, ICAR Newsletter. 2010; 16 (4): 6-7.

- Raina A. P. and Negi K. S. Essential oil composition of Origanum marjoram and Origanum vulgare hirtum growing in India. Chem. Natu. Comp. 2012;47(6):1015-1017.

CrossRef - Pande C., Tewari G., Singh S., Singh C. Chemical markers in Origanum vulgare from Kumaon Himalayas: a chemosystematic study. Natural Products Research. 2012; 26(2):140-145.

CrossRef - Verma R.S., Padalia R.C, Chauhan A. Volatile constituents of Origanum vulgare, ‘thymol’ chemotype: variability in North India during plant ontogeny. Natural Products Research.2012; 26(14):1358-1362.

CrossRef - Negi K. S., Ojha S. N., Koranga S. S., Rawat K. S., Pandey M. M., and Raina A. P. NKO-68 (IC 589087/INGR13046) Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) for high percentage of phenolic compound thymol and high yield of essential oil. Indian J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2013;26(3): 259-260.

- Ojha N. S., Negi K. S., Tewari L. M. Studies on ecological, taxonomic, ethnobotanical and chemotypic variation in ‘OREGANO’ (Origanum vulgare ) and prospects of its cultivation, Thesis. 2014; 1-416.

- Aligiannis N., Kalpoutzakis E., Mitaku S., Chinou I. B. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of two Origanum Agri. Food Chem. 2001; 49: 4168-4170.

CrossRef - Letswaart J. H. A taxonomic revision of the Genus Origanum. Leiden University Press The Hague / Boston / London. 1980; 3(5):1-149.

- Sahin F., Gulluce M., Deferera D., Sokmen A., Sokmen M., Polissiou M., Agar G., Ozer H. Biological activities of the essential oils and methanol extract of Origanum vulgare vulgare in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. Food Control. 2004; 15(7): 549–557.

CrossRef - Sivicka I., Adamovies A., Ivanovs S., Oniska E.Some morphologicaland chemical characteristics of Oregano (Origanum vulgare) in Lativa.Agronomy Res 17: 2064-2070Biotechnol Equip. 2019;23:1322-1324.

- Weglarz Z., Kosakowska O., Przybył J., Pioro-Jabrucka E., Katarzyna B. The quality of Greek oregano ( vulgare L. subsp. hirtum (Link)Ietswaart) and common oregano (O. vulgare L. subsp. vulgare) cultivated in the temperate climate of Central Europe. Foods. 2020; 9: 1671.

CrossRef - Sarrou E., Tsivelika N., Chatzopoulou P., Tsakalidis G., Menexes G., Mavromatis A. Conventional breeding of Greek oregano (Origanum vulgare hirtum) and development of improved cultivars for yield potential and essential oil quality. Euphytica. 2017; 213(5).

CrossRef - Naithani N. B. Flora of Chamoli District. Vols. I & II. Botanical Survey of India, Howrah. 1985.

- Radusiene J., Stankeviciene D., Venskutonis R.Morphological andchemical variation of Origanum vulgare from Lithuania, In: Beranth, J., Nemth, E., Craker, L.E., Gardner, Z. E. (Eds.) Bioprospecting &Ethnopharmacology. Proc. WOCMAP III. Acta Hort. 2005; 1: 675.

- Lotti , Ricciardi L., Rainaldi G., Ruta C., Tarraf W., De Mastro G . Morphological, Biochemical, and Molecular Analysis of O. vulgare L. The open agriculture journal. 13(1):116-124.

CrossRef - Kuniyal C. P., Bhadula S. K. and Prasad P. Morphological and biochemical variations among the natural populations of Aconitum atrox (Bruhl) Muk. (Ranunculaceae). Plant Biol. 2002; 29(1): 1-5.

- Gales R.C., Preotu A., Necula R., Gille E., Toma C. Altitudinal variations of morphology, distribution and secretion of glandular hairs in vulgare L. leaves. Studia Universitatis Vasile Goldis Arad, Seria Stiintele Vietii. 2010;20(1):59-62.

- Licina B., Stefanovic O., Vasic S., Radojevic I., Dekic M. Biological activities of the extracts from wild growing Origanum vulgare Food Control. 2013; 33: 498-504.

CrossRef - Kofidis G., Bosabalidis A.M., Moustakas M. Contemporary seasonal andaltitudinal variations of leaf structural features in oregano (Origanum vulgare). Ann Bot. 2003; 92: 635-645.

CrossRef - Gales R., Toma C., Preotu A. and Gille E. Structural peculiarities of the vegetative apparatus of spontaneous and cultivated vulgare L. plants. Analele Stiintificeale Universitatii din Craiova. 2008; 13(41): 273-278.

- Pimple B. P., Patel A. N., Kadam P. V., and Patil M. J. Microscopic evaluation and physicochemical analysis of Origanum majorana Linn leaves. Asian Pacif. J. Tropi. Dise. 2012; 897-903.

CrossRef - Maithani A., Maithani U., Singh M. Morphological and Anatomical Characterization of Genotypes of Origanum vulgare Journal of Plant Science and Research.2022; 9(2): 233.

- Lukas B., Schmiderer C., Novak J. Essential oil diversity of European Origanum vulgare (Lamiaceae). Phytochemistry. 2015; 119: 32-40.

CrossRef - Rechinger K.H.Die Flora von Euboea. Teil Botanische Jahrbucher fur Systmatik, Pflanzengeschichte und pflanzengeographie 1961; 80 (3): 294-382.

- Putievsky E. Temperature and day length influences on the growth and germination of sweet basil and Oregano. Hort. Sci. 1983; 58: 583-587.

CrossRef - Kaul M. L. H. Male Sterility in Higher Plants. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, London, Paris, Tokyo.1988.

- Lewis D. and Crowe L. K. Male sterility as an outbreeding mechanism in Origanum vulgare. Heredity Abstr. 1952; 6:136.

- Kheyr-Pour A. Nucleo-cytoplasmic polymorphism for male sterility in Origanum vulgare Heredity. 1980; 71:253-260.

CrossRef - Bernath J., Novak I., Szabo K., Seregely Z. Evaluation of selected Oregano (Origanum vulgare subsp. Hirtum Letswarrt) lines with traditional methods and sensory analysis. Herbs Spices Medicinal Plants. 2006; 11:19-26.

CrossRef - Torres L. E., Brunetti P. C., Baglio C., Bauza P. G., Chaves A. G., Massuh Y., Ocano S. F. and Ojeda M. S. Field evaluation of twelve clones of Oregano grown in the main production areas of Argentina: Identification of quantitative trait with the highest discriminant value. ISRN Agronomy. 2012; 1-10.

CrossRef - Franz C., Novak J. part IV- Cultivation and breeding: breeding of Oregano. In: Kintzois SE(ed) Oregano: The genera Origanum and Taylor and Francis, Milton park. 2002a; 163-167.

- Franz C., Novak J. Breeding of oregano. In: Spiridon E(ed) Oregano: The genera Origanum and Taylor and Francis, CRC press. 2002b; 163-167.

- Goliaris A.H., Chatzopoulou P.S., Katsiotis S.T. Production of new Greek Oregano clones and analysis of their essential oils. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2002; 10:29–35.

CrossRef - Chatzopoulou P., Bosmali E., Ganopoulos I., Sarrou E., Madesis P., Koutsos T. Morphological, biochemical and genetic characterization of Greek Oregano selected genotypes (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum). In 15th conference of Hellenic Scientific Society for Genetics and Plant Breeding, Proceeding, 2014: 318-322.

- Pank F., Experiences with descriptors for characterization of medicinal and aromatic plants. Plant Genet Resour. 2005; 3:190–198

CrossRef - Collard B. C. Y., Mackill D. J. Marker-assisted selection: an approach for precision plant breeding in the twenty-first century. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2008; 363(1491): 557-572.

CrossRef - Ben-Ari G., Lavi U. Marker-assisted selection in plant breeding. Plant Biotechnology and Agriculture: Prospects for the 21st Century. 2012;163-184.

CrossRef - Nybom, H. & Weising, K. DNA profiling of plants. In: Medicinal plants biotechnology, from basic to industrial applications, O. Kayser & W. J. Quax. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. 2007; 73

CrossRef - Klocke E., Langbehn J., Grewe C., Pank F. DNA Fingerprinting by RAPD on Origanum majorana Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2002; 9:171–176

CrossRef - Katsiotis A., Nikoloudakis N., Linos A., Drossou A., Constantinidis T. Phylogenetic relationships in Origanum based on rDNA sequences and intra-genetic variation of Greek O. vulgare subsp. hirtum revealed by RAPD. Sci. Hortic. 2009;121(1): 103-108.

CrossRef - Novak J., Lukas B., Bolzer , Grausgruber-Groger S., Degenhardt, J.Identification and characterization of simple sequence repeat markers from a glandular Origanum vulgare expressed sequence tag. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2008; 8(3), 599-601.

CrossRef - Helsen K., Jacquemyn H., Hermy M., Vandepitte K., Honnay O. Rapid buildup of genetic diversity in founder populations of the Gynodioecious plant species vulgare after semi-natural grassland restoration. PLoS One. 2013;8

CrossRef - Azizi A., Wagner C., Honermeier B., Friedt W. Intraspecific diversity and relationship between subspecies of vulgare revealed by comparative AFLP and SAMPL marker analysis. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2009; 281(1-4):151-160.

CrossRef - Azizi A., Hadian J., Gholami M., Friedt W., Honermeier B. Correlations between genetic, morphological, and chemical diversities in a germplasm collection of the medicinal plant Origanum vulgare Chemistry and Biodiversitry. 2012:9(12):2784-2801.

CrossRef - Van Looy K., Jacquemyn H., Breyne P., Honnay O. Effects of flood events on the genetic structure of riparian populations of the grassland plant Origanum vulgare. Biological Conservation. 2009; 142: 870-878.

CrossRef - Amar M. H., Wahab M., Abd E. Comparative genetic study among Origanum L. plants grown in Egypt. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences. 2013;3(12):208-222.

- Jedrzejczyk I. Study on genetic diversity between Origanum species based on genome size and ISSR markers. Indus trial Crops and Products. 2018;126:201-207.

CrossRef - Bansleben A. C., Schellenberg I., Einax J.W., Schaefer K., Ulrich D. Chemometric tools for identification of volatile aroma active compounds in Oregano. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009; 395:1503– 1512.

CrossRef - Baranauskiene R., Venskutonis P.R., Dewettinck K., Verhe R. Properties of Oregano (Origanum vulgare), citronella (Cymbopogon nardus G.) and marjoram (Majorana hortensis L.) flavors encapsulated into milk protein-based matrices. Food Res Int. 2006;39:413–425.

CrossRef - Nhu-Trang T.T., Casabianca H., Grenier-Loustalot M.F. Deuterium/hydrogen ratio analysis of thymol, carvacrol, cterpinene and p-cymene in thyme, savory and Oregano essential oils by gas chromatography-pyrolysis-isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Chromatogr. 2006;1132:219–227.

CrossRef - Sokovic M., Glamoclija J., Marin P.D., Brkic D., Griensven L.J. Antibacterial effects of the essential oils of commonly consumed medicinal herbs using an in vitro model. Molecules. 2009; 15:7532-7546.

CrossRef - Mishra P. and Mishra S. Study of antibacterial activity of Ocimum sanctum extract against gram positive and gram negative bacteria. Amer. J. Food Technol. 2011; 6: 336-341.

CrossRef - Cava R., Nowak E., Taboada A. and Marin-Iniesta F. Antimicrobial activity of Clove and Cinnamon essential oils against Listeria monocytogenes in Pasteurized Milk. J. Food Protec. 2007; 70: 2757-2763.

CrossRef - Hussain A. I., Anwar F., Sherazi S. T. H. and Przybylski R. Chemical composition, Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of basil (Ocimum basilicum) essential oils depends on seasonal variations. Food Chem. 2008; 108: 986-995.

CrossRef - Hajhashemi V., Ghannadi A. and Sharif B. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of the leaf extracts and essential oil of Lavandula angustifolia J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003; 89: 67-71.

CrossRef - Anwar F., Hussain A. I., Sherazi S. T. H., Bhanger M. I. Changes in composition and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) fruit at different stages of maturity. J. Herbs, Spices Medi. Plants. 2009; 15: 1-16.

CrossRef - Tibaldi G., Fontana E., Nicola S. Growing conditions and postharvest management can affect the essential oil of Origanum vulgare ssp hirtum (Link) Ietswaart. Industrial Crops and Products. 2011;34(3), 1516-1522.

CrossRef - Baranauskiene R., Venskutonis P. R., Dambrauskiene E., Viskelis P. Harvesting time influences the yield and oil composition of vulgare L. ssp vulgare and ssp hirtum. Industrial Crops and Products. 2013; 49:43-51.

CrossRef - Morshedloo M. R., Craker L. E., Salami A., Nazeri V., Sang H., Maggi, F. Effect of prolonged water stress on essential oil content, compositions and gene expression patterns of mono- and sesquiterpene synthesis in two oregano (Origanum vulgare) subspecies. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017; 111:119-128.

CrossRef - Kokkini, S., Karousou, R., Hanlidou, E. & Lanaras, T. Essential oil composition of Greek (Origanum vulgare hir-tum) and Turkish (O. onites) Oregano: a Tool for Their Distinction. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 2004;16 (4): 334-338.

CrossRef - Prieto J.M., Iacopini P., Cioni P. and Chericoni S. In vitro activity of the essential oils of Origanum vulgare, Satureja montana and their main constituents in peroxynitrate induced oxidative processes. Food Chemistry. 2007;104: 889-895.

CrossRef - Dimitrijevic S.I., Mihajlovski R.K., Antonovic D.G., Milanovic-Stevanovic M.R. and Mijin, D.Z. A study of the synergistic antilisterial effects of a sub-lethal dose of lactic acid and essential oils from Thymus vulgare, Rosemarinus officinalis L. and Origanum vulgare L. Food Chemistry. 2007; 104: 774-782.

CrossRef - Baser K.Biological and pharmacological activities of carvacrol and carvacrol bearing essential oil.Current Pharmaceutical Design.2008;14(29):3106-19.

CrossRef - Kowalczyk A., Przychodna M., Sopata S., Bodalska A., Fecka I. Thymol and thyme essential oil – new insights into selected therapeutic uses.Molecules.25(4125):1-17.

CrossRef - Kamatou G., Vilijoen A. Linalool: A review of biologically active compound of commercial importance.Natural product communication.2008;3(7):1183-1192.

CrossRef - Vieira A.J., Beserra M.C., Souza B.M., Tottin A.L.Limonene : Aroma of innovation in health and disease. Chemico-Biological Interactions.2017;283:97-106.

CrossRef - Masyita A., Sari R.S., Astuti A. D., Yasir B., Rumata N. R.,Emran T. B., Nainu F., Gandra J.S. Terpinene and terpinoids as main bioactive compounds of essential oils, their roles in human health and potential application as natural food preservative.Food chemistry:X.2022;13:100217.

CrossRef - Marchese A., Arciola C.R., Barbieri R. Update on monoterpene as antimicrobial agents:A particular focus on p-cymene. Materials.2017; 10(8).

CrossRef - Armengol G.F., Filella I., Llusia J., Penuelas J.,Β-Ocimene , a key floral and foliar volatile involved in multiple interactions between plants and other organisms.Molecules. 2017;22(1148):1-9.

CrossRef - Khaleel C., Tabanca N., Buchbauer G. Terpineol , a natural monoterpenne: A review of its biological properties.Open chem. 2018;16:349-361.

CrossRef - Ryu Y., Lee D., Jung C., Lee K. J., Jin H., Kin S.J., Lee H.M., Kim B., Won K.J.Sabinene prevents skeletal muscle atrophy by inhibiting the MAPK-MuRF-1 pathway in rats.International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(4955):1-14.

CrossRef - Benchikha N., Lanez T., Menaceur M., Barhi Z. Extraction and antioxidant activities of two species of Origanum plant containing phenolic and flavonoid compounds. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences. 2013; 5(1):120-128.

CrossRef - Fei H., Guang-qiang M., Ming Y., Li Y., Wei X., Ji-cheng S. Chemical composition and antioxidant activities of essential oils from different parts of the oregano. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B (Biomed & Biotechnol). 2017;18 (1):79-84.

CrossRef - Gayoso L., Roxo M., Cavero R. Y., Calvo M. I., Ansorena D., Astiasaran I., Wink M. Bioaccessibility and biological activity of Melissa officinalis, Lavandula latifolia and Origanumvulgare extracts: Influence of an in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018; 44:146-154.

CrossRef - Teixeria B., Marques A., Ramos C., Serrano C., Matos O., Neng N. R., Nogueria J. M. F., Saraiva J. A, Nunes M. L. Chemical composition and bioactivity of different Oregano (Origanum vulgare) extracts and essential oil. Food and Agriculture. 2013; 93:2707-2714.

CrossRef - Leyva-Lopez N., Gutierrez-Grijalva E. P., Vazquez-Olivo G., Heredia J. B. Essential oils of Oregano: Biological activity beyond their antimicrobial properties. Molecules. 2017; 22(6): 989.

CrossRef - Baricevic D., Milevoj L. and Borstnik J. Insecticidal effect of Oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum Letswaart) on the dry bean weevil (Acanthoscelides obtectus Say). Horticultural Sci. 2001; 7(2):84–88.

CrossRef - Tuncer E., Unver-Saraydin S., Tepe B., Karadayi S., Ozer H., Karadayi K., Turan M. Antitumor effects of Origanum acutidens extracts on human breast cancer. Journal of BU ON.: official journal of the BUON (Bssalkan Union of Oncology). 2013; 18(1): 77-85.

- Gattia K.J. Effects of O vulgare on some sperms parameters, biochemical and some hormones in alloxan diabetic mice. Journal of Wassit for Science & Medicine. 2009; 2(1):11-29.

- Khaki M.R.A., Pahlavan Y., Sepehri G., Sheibani V., Pahlavan B. Antinociceptive effect of aqueous extract of vulgare L. in male rats: possible involvement of the GABAergic System. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2013; 12(2):407-413.

- Gholamhoseinian A., Shahouzehi B., Sharififar F. Inhibitory effect of some plant extract on pancreatic lipase. Intenational Journal of Pharmacology. 2010; 6:18-24.

CrossRef - Coqueiro D.P., Bueno P.C.S., Guiguer E.L., Barbalho S.M., Souza M.S.S., Araujo A.C. Effects of oregano(Origanum vulgare) tea on the biochemical profile of wistar rats. Scientia Medica. 2012; 22(4):191-196

- Sikander M., Malik S., Parveen K., Ahmad M., Yadav D., Hafeez Z.B., Bansal M. Hepatoprotective effect of Origanum vulgare in Wistar rats against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity. Protoplasma. 2012; 250(2):483-493.

CrossRef - Emadi L., Azari O., Sakhaee E., Talebian M., Azami E., Shaddel M. Protective effect of ethanolic extract of vulgare on halothane-induced hepatotoxicity in rat. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Surgery. 2008; 3(3):29-37.

- Mitchell T.C., Stamford T.L.M., Souza E.L.d., Lima E.d.O., Carmo E.S. Origanum vulgare essential oil as inhibitor of potentially toxigenic Aspergilli. Ciencia e Tecnologia de Alimentos. 2010; 30(3):755-760.

CrossRef - Ashraf Z., Muhammad A., Imran M., Tareq A. In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity of methanol, chloroform and aqueous extracts of analysis. International Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2011; 1(4):257-261.

CrossRef - Bedoya-Serna C.M., Dacanal G.C., Andrezza M., Fernandes A.M., Samantha C., Pinho S.C. Antifungal activity of nanoemulsions encapsulating oregano ( vulgare) essential oil: in vitro study and application in Minas Padrao cheese. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2018; 49:929-935.

CrossRef - Busatta C., Mossi A.J., Rodrigues M.R.A., Cansian R.L., Oliveira J.V. Evaluation of vulgare essential oil as antimicrobial agent in sausage. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2007; 38:610-616.

CrossRef - Khan A., Bashir S., Khan S.R., Gilani A.H. Antiurolithic activity of vulgare is mediated through multiple pathways. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011; 11(1):96.

CrossRef - Ding H.Y., Chou T.H., Liang C.H. Antioxidant and antimelanogenic properties of rosmarinic acid methyl ester from Origanum vulgare. Food Chemistry. 2010; 123 (2):254- 262.

CrossRef - Mbaye M.M., El Khalfi B., Addoum B., Mar P.D., Saadani B., Louanjli N., Soukri A. The Effect of Supplementation with Some Essential Oils on the Mobility and the Vitality of Human Sperm. Sci. World J. 2019.

CrossRef - Tognolini M., Barocelli E., Ballabeni V., Bruni R., Bianchi A., Chiavarini M. Comparative screening of plant essential oils: phenylpropanoid moiety as basic core for antiplatelet activity. Life Science. 2006; 78(13):1419-1432.

CrossRef - De Mastro, G., Fracchiolla, M., Verdini, L. & Montemurro, P. Oregano and its potential use as bioherbicide. Acta Horticulturae. 2006; 723:335-345.

- Bansleben A. C., Schellenberg I., Einax J.W., Schaefer K., Ulrich D. Chemometric tools for identification of volatile aroma active compounds in Oregano. Anal Bioanal Chem.2009; 395:1503– 1512.

CrossRef - Nosal P., Kowalska D., Bielanski P., Kowal J., Kornas S. Herbal formulations as feed additives in the course of rabbit subclinical coccidiosis. Ann. Parasitol. 2014; 60(1), 65-69.

- Skoufos I., Tsinas A., Giannenas I., Voidarou C., Tzora A., Skoufos J. Effects of an Oregano based dietary supplement on performance of broiler chickens experimentally infected with Eimeria Acervulina and Eimeria Maxima. Poultry Science. 2011; 48(3), 194-200.

CrossRef - Hussain A. I., Anwar F., Sherazi S. T. H. and Przybylski R. Chemical composition, Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of basil (Ocimum basilicum) essential oils depends on seasonal variations. Food Chem. 2008; 108: 986-995.

CrossRef - Santoro G. F., Cardoso M. D. G., Guimaraes L. G., Salgado A. P., Menna-Barreto R. F. , Soares, M. J. Effect of oregano (Origanum vulgare) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) essential oils on Trypanosoma cruzi (Protozoa: Kinetoplastida) growth and ultrastructure. Parasitology Research. 2007; 100(4), 783-790.

CrossRef - Machado M., Dinis A. M., Salgueiro L., Cavaleiro C., Custodio J. B. A., Sousa M. d. C. Anti-Giardia activity of phenolic-rich essential oils: effects of Thymbra capitata, Origanum virens,Thymuszygis sylvestris, and Lippia graveolens on trophozoites growth, viability, adherence, and ultrastructure. Parasitology Research. 2010; 106(5):1205-1215

CrossRef - Gaur S., Kuhlenschmidt T. B., Kuhlenschmidt M. S., Andrade J. E. Effect of Oregano essential oil and carvacrol on Cryptosporidium parvum infectivity in HCT-8 cells. Parasitology International. 2018; 67(2), 170-175.

CrossRef - Karamanos A. J., Sotiropoulou D. E. K. Field studies of nitrogen application on Greek Oregano (Origanum vulgare ssp. Hirtum (link) Letswaart) essential oil during two cultivation seasons. Industrial Crops and Products. 2013; 46: 246-252.

CrossRef - Dordas C. Foliar application of calcium and magnesium improves growth, yield, and essential oil yield of Oregano (Origanum vulgare Hirtum). Industrial Crops and Products. 2009; 29: 599-608.

CrossRef - Chauhan N. K., Singh S., Haider S. Z., Lohani H. Influence of phenological stages on yield and quality of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) under the agroclimatic condition of Doon valley (Uttarakhand). Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Science. 2013; 75 (4):489-493.

CrossRef