Introduction

The vision conceived by the Sikkim’s Chief Minister in the year 2003 is not unfamiliar to India. A popular talk show, “Satyamev Jayate,” hosted by Aamir Khan in 2012 played a key role in introducing millions of Indian viewers to a groundbreaking government initiative in Sikkim, amidst rising worries concerning the use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers in agriculture, Sikkim’s Organic Mission has become a global topic of conversation. By 2015 this programme aims to renovate Sikkim into a completely organic State, ensuring that all agricultural harvest from the state is cultivated using organic composts and is safe for human consumption. While Cuba may be remembered as the first country to adopt large-scale organic farming, its adoption was largely driven by necessity due to longstanding trade embargoes.1 In contrast, Sikkim voluntarily embraced organic farming under the visionary leadership of the Hon’ble Chief Minister, establishing itself as a democratic model for organic farming worldwide. Sikkim was the first state n the country to officially adopt and become a totally organic agriculture state by the end of 2015.2 The foundation of the organic state was passed by Sikkim Legislative Assembly through a resolution to adopt organic farming but t was delayed and again started on 15th august and almost 74000 ha land area of entre state has been certified as organic agriculture area.2 The organic cultivation of Sikkim, predominantly comprising vegetables, not only assures greater financial rewards for Sikkimese agriculturists but also presents multifarious advantages to the state. The organic certification is positioned to complement Sikkim’s ecotourism endeavors, another pioneering initiative of the Honorable Chief Minister. Industry participants in Sikkim foresee that blending the Organic Mission with ecotourism will draw visitors, particularly to home-based accommodations, offering sojourners the dual appeal of Sikkim’s pristine natural landscapes and the health advantages of organic goods, thereby augmenting the worth of Sikkim’s ecotourism. Since 2003, the Government of Sikkim has been actively involved in the Organic Mission, halting imports of chemical fertilizers and fostering a culture of organic farming among Sikkimese farmers, who traditionally rely on organic manure. To promote Sikkim’s organic products, the government has initiated Sikkim organic retail stores in Delhi and strategies to expand to main metropolises across India.3 Imagine a revolution in organic farming—one that enriches soil instead of depleting it and preserves seed rather than depletes it. At the forefront of this movement are millions of women who envision a sustainable tomorrow. Their tireless efforts are reshaping our world. Women who farm stands in solidarity with these change makers, offering resources, community, and shared narratives.

Agri-tourism, also known as agro-tourism, is a niche tourism sector that encompasses various agriculturally based activities, including farm stays, direct produce purchases, corn mazes, animal feeding, and farm-based bed and breakfasts. This form of tourism is recognized as a burgeoning industry in many countries like Australia, Canada, USA, and the Philippines, contributing to rural development and sustainable agriculture. In India, Agriculture Tourism has been operational since 2004, starting with the Baramati Agri Tourism centre under the guidance of Pandurang Taware, who was honoured with the National Tourism Award for his contributions. Is agro-tourism, a development strategy for rural areas combined with sustainable-environmental practices, a viable solution for rural areas in alleviating poverty? The role of agro-tourism in growth, amidst existing challenges faced by rural communities and the imperative of sustainable development and women’s empowerment, has been examined within the context of a project, and results are discussed herein.

These objectives provide a structured framework for analyzing the multifaceted roles of women in agricultural and household activities, their decision-making influence, and their perspectives on agricultural tourism, ultimately aiming to identify strategies for empowerment and community development.

Objectives

This study aims to

Investigate the social and background characteristics (demographic characteristics) of women involved in farming and household chores.

Identify the primary agricultural tasks and domestic responsibilities that women handle.

Evaluate the extent of women’s participation in decision-making related to farm activities and household management.

Explore women’s knowledge, attitudes, and interest in agri-tourism as a potential avenue for economic empowerment.

Assess the challenges and opportunities women face in balancing agricultural work, domestic duties, and potential involvement in agri-tourism.

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant relationship between women’s age and their involvement in different agricultural activities.

Hypothesis 2: Women who spend more hours on agricultural tasks face greater challenges in balancing household responsibilities.

Hypothesis 3: Women’s participation in agricultural decision-making processes is significantly influenced by their education level.

However, before delving into the paper findings, we should summarize the recent developments in the realm of agro-tourism.

Understanding Organic Agro-Tourism as a Rural Progress Approach

Rural development serves as a political strategy to bridge socio-cultural and economic disparities between rural and urban regions, aiming to enhance the livelihoods of rural communities and address issues such as migration and unemployment in situ.4 It encompasses initiatives that elevate the living standards and prosperity of rural populations in a sustainable manner, thereby mitigating rural poverty indirectly through employment generation and increased demand beyond agriculture, while also narrowing regional income differentials and stemming rural-to-urban migration.5 Turkey, with approximately 35% of its populace residing in rural areas and experiencing per capita incomes merely 40% of those in urban counterparts, underscores the criticality of rural development amidst challenges like inadequate infrastructure, healthcare, and educational services, fragmented agricultural establishments, and limited employment opportunities, particularly for youth and women.4

Drawing insights from tourism data and emphasizing tourism’s significance in impoverished nations,6 accentuate tourism’s potential to serve as a livelihood for many of the world’s underprivileged. They highlight tourism’s capacity to generate employment and supplemental income, noting its symbiotic relationship with agriculture, which has propelled agro-tourism to the forefront as an innovative agricultural pursuit. In Europe, rural tourism assumes a pivotal role, exemplified by regions like Wittow in East Germany, where 80% of accommodations derive from working farms or farm conversions into lodging facilities.7 Poland’s experience underscores the efficacy of rural farm-based tourism as a cost-effective approach utilizing existing farm infrastructure and basic catering amenities.7

Rural tourism, both domestically and internationally, has garnered considerable attention, characterized by its location, scale, and alignment with the multifaceted rural environment, economy, history, and context. 8 Notably, agro-tourism emerges as a significant contributor to preserving rural landscapes and cultural heritage, curbing migration, augmenting income, and diversifying household economic activities.9 and, underscore agro-tourism’s role in revitalizing local economies. In China, rural tourism has catalyzed economic transformation, enhancing farmers’ incomes, revitalizing rural industries, and fostering environmental consciousness and cultural appreciation. 8 Agro-tourism, a subset of rural tourism, emerges as a promising strategy for bolstering agricultural incomes and revitalizing rural communities.10 It facilitates the rediscovery of neglected rural resources and engenders economic upliftment through diverse agro-tourism models, as evidenced by comparative studies across nations like Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Norway.11 Fostering cultural exchanges and offering authentic rural experiences, agro-tourism satisfies tourists’ yearning for genuine rural lifestyles and landscapes, thus presenting an alternative to conventional tourism paradigms.12 Despite its potential, agro-tourism grapples with challenges like information asymmetry, insufficient venture capital, and the absence of cooperative organizations.13

The goals for this study, are to understand the need and importance of Organic agro-tourism in Womens Empowerment and development in Sikkim and to determine their position. To guarantee the long-term sustainability and continued relevance of agro-tourism, this assessment will meticulously evaluate the aforesaid elements and provide actionable recommendations.

To understand agro-tourism’s capacity to alleviate poverty and generate jobs.

To study socioeconomic and demographic factors of rural women.

To understand potential contributions of agro-tourism activities towards women’s empowerment.

The Role of Women in Rural Development

In Sikkim, women play a pivotal role in rural development, their empowerment serving as a cornerstone for sustainable progress. Women’s empowerment is not only essential for gender equality but also vital for enhancing the overall well-being of rural communities. By empowering women, rural development initiatives gain access to a broader pool of talent, creativity, and leadership, thereby fostering more inclusive and comprehensive approaches to community development. Moreover, women’s empowerment in rural areas contributes to breaking the cycle of poverty by enabling them to participate more actively in decision-making processes, access education and healthcare, and generate income to support their families.

However, women in traditional agriculture often face multifaceted challenges that hinder their full participation and empowerment. A multitude of factors impede women’s ability to fully contribute to the agricultural sector. These limitations include restricted access to land and essential resources, coupled with a lack of participation in decision-making processes. Furthermore, inadequate educational and training opportunities restrict their potential for professional development. Cultural norms and ingrained gender stereotypes can exacerbate these challenges, acting as significant barriers that prevent women from effectively leveraging their skills and knowledge within agriculture. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive strategies that address structural inequalities, promote gender-sensitive policies, and provide targeted support to women farmers. Despite these challenges, there are numerous examples of successful female-led initiatives driving rural development in Sikkim. These initiatives range from women’s cooperatives engaged in organic farming and agro-processing to community-based organizations promoting sustainable agriculture and eco-tourism. By showcasing the leadership, resilience, and innovation of women in rural communities, these case studies highlight the transformative potential of women’s empowerment in driving inclusive and sustainable development. Moreover, they underscore the importance of investing in women’s education, skills development, and access to resources to unlock their full potential as agents of change in rural development efforts.

Promoting Women’s Livelihoods in Organic Agriculture

The integration of organic agro-farming and empowerment of Womens’ in Sikkim holds immense potential for fostering sustainable rural development and gender equality. By engaging women in organic farming practices, communities can harness the numerous benefits that organic agriculture offers, including improved soil health, reduced environmental impact, and enhanced food security. Moreover, organic farming empowers women by providing them with opportunities for meaningful participation in agricultural activities, decision-making processes, and income generation. Through their involvement in organic farming initiatives, women gain access to valuable resources, skills, and knowledge, enabling them to contribute more effectively to household livelihoods and community development.

To involve women in organic agro-tourism in Sikkim, strategic approaches are needed to overcome barriers and maximize opportunities. One strategy involves providing women with training and capacity-building programs focused on organic farming techniques, agro-processing, and eco-tourism management. Additionally, creating supportive policies and incentives that prioritize women’s participation and leadership in organic agro-tourism initiatives can help promote gender equality and empower women in rural communities. However, potential challenges such as limited access to resources, social and cultural norms, and market barriers may impede women’s participation in organic agro-tourism. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach that includes targeted interventions, awareness-raising campaigns, and collaboration with local stakeholders to create an enabling environment for women’s empowerment in the organic farming and agro-tourism sectors.

Sustainable Rural Renaissance Through Organic Agro-Tourism.

In Sikkim, organic agro-tourism exemplifies the fusion of ecological preservation, economic growth, and social empowerment, heralding a transformative era for rural communities. This initiative has significantly enhanced rural livelihoods by promoting sustainable agricultural practices, protecting local ecosystems, and creating economic opportunities. The rising demand for organic produce and experiential tourism has increased rural incomes and fostered entrepreneurship and job creation. Socially, it has empowered marginalized groups, especially women, by involving them in agricultural value chains and community tourism enterprises. Environmentally, these initiatives have encouraged biodiversity conservation, soil health, and water preservation, thus enhanced local ecosystem resilience, and reduced the negative impacts of conventional farming. Success stories like Ms. Tenzing Dolma’s thriving agro-tourism farm and the Sangha Women’s Cooperative highlight women’s critical role in sustainable rural development. Their achievements underscore the importance of access to training, resources, and support networks. Sikkim’s government policies, such as the pioneering Organic Mission of 2003, have been instrumental in promoting organic farming and agro-tourism. These policies provide technical assistance, halt chemical imports, and support infrastructure development, financial incentives, and marketing, thereby fostering sustainable economic growth and improved livelihoods.

Materials and Methods

In Sikkim, only some villages are truly very fruitful in running organic agro-tourism concept. For that reason, some villages of East Sikkim have been selected as the model area. The information for this research was gathered through a field survey conducted in these selected villages.

|

Image 1: Study materials of Sikkim. |

The Interviews with Women Volunteers of Sample the Village

Interviews were done with women volunteers from self-help group, Farm School, and farm stay of East District of Sikkim. Some villages with probable for agro-tourism were recognized and field surveys were conducted in those villages. Several factors ultimately influenced the selection of the pilot region for this study. These factors included the untouched air and water quality, the assorted agricultural produce, the availability of basic healthcare conveniences, and, most crucially, the keen essence demonstrated by the women, village council, and the residents. The following villages were selected as the pilot region of this study, with a sample of 100 women from each pilot region area which makes a total of 500 sample size.

Khamdong

Zuluk

Sazong-Rumtek

Pakyong

Lingdok

The Composition of the Sample Volume

Data collection for this study involved face-to-face interviews with women residing in the pilot region, all above the age of twenty. The interviews utilized standardized questionnaires designed to capture information relevant to the participants’ socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. This approach ensured consistency in data collection and facilitated analysis to assess the influence of these factors on the potential impact of agro-tourism.

Forming of the Questionnaire

The purpose of the questions was to understand Women’s Role in Agricultural and Household Activities, Participation in Decisions, and Approach to Agricultural Tourism: The questionnaire was composed of six main parts.

Demographic Information

Agricultural Activities

Household Responsibilities

Participation in Decision-Making

Approach to Agricultural Tourism

Challenges and Opportunities

Data analysis

Following data collection through standardized questionnaires, a rigorous data analysis process was undertaken and the analysis method developed by Peter Rogerson was used.16 The data was first coded to facilitate statistical analysis using the SPSS software package. Descriptive statistics and chi-square analyses were then employed to assess the data and identify any statistically significant relationships between the variables of interest. To ensure the validity of the findings, the data derived from the questionnaires were further corroborated by observations made during the face-to-face interviews. This multifaceted approach to data analysis enhanced the overall robustness of the research and yielded reliable insights.

|

Image 2: Opportunities of Organic Agro Tourism |

Results and Discussion

Women’s Approach to Agro Tourism in the Study Area

The study identified a limited understanding of tourism among the women, with “tourists” solely associated with foreign visitors. Despite being unfamiliar with terms like “agri-tourism,” “farm-focused tourism,” or even “environmentally friendly tourism,” a significant portion of the women expressed interest in developing tourism opportunities in their villages. This study revealed a noteworthy association (p < 0.05) between a woman’s level of educational attainment and her propensity to support increased tourist access to villages. A resounding 88.2% of female participants expressed a fervent desire for their communities to become more welcoming to visitors and foster tourism development. Education level played a role in women’s views on tourism development. Women with limited or primary education were less expected to support opening the village to tourists. Additionally, a woman’s spouse’s occupation influenced her perspective.14 Wives of officials or business owners (shopkeepers) were more inclined to favor increased tourism in their villages. Among women endorsing village openness to tourism, a significant motivator was anticipated village development. 70.6% expressed a belief that increased tourist access would lead to advancement. Furthermore, 17.6% of these women identified the potential for cultural exchange (meeting new people) as a noteworthy benefit. The possibility of increased sales of handicrafts was also a factor, with 11.8% of these women citing this as an advantage.

|

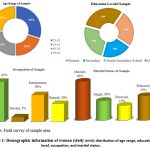

Figure 1: Demographic information of women (study area) distribution of age range, education level, occupation, and marital status. |

Source: Field survey of sample area.

The table 1. provides a snapshot of a sample population which is categorized by age, education level, marital status, livelihood.

Age Distribution

25-35: Largest group at 30%, indicating a youthful demographic, 35-45: Smallest group at 20%, 45-55 and 55-65: Both make up 25%, showing a balanced presence of middle-aged and older individuals.

Marital Status

Married: Dominates at 40%, suggesting a societal preference for marriage, Single: 20%, a significant portion not in marital relationships, followed by Divorced: 15%, indicating marital dissolution, and Widowed: 25%, reflecting an aging population with spousal loss.

Education Level

Primary School: 25%, highlighting limited educational attainment for a significant segment, Secondary School: 20%, and Senior Secondary School: 25%, indicating intermediate education levels, and Graduate: 30%, suggesting a substantial portion with higher education.

Occupation

Farmer: Largest group at 45%, pointing to an agrarian-based economy, Entrepreneur: 30%, showing a strong entrepreneurial presence, retired: 20%, indicating a significant non-working population, and Teacher: 5%, the smallest group, suggesting a limited education sector workforce.

Synthesis

The sample is predominantly youthful and married, with a diverse educational background. Farming is the main occupation, complemented by a significant number of entrepreneurs. The presence of a substantial retired population and varied education levels highlights the need for tailored social and economic policies to address these diverse segments.

|

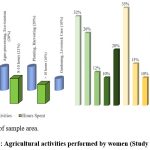

Figure 2: Agricultural activities performed by women (Study area). |

Source: Field survey of sample area.

The table 2. provides a comprehensive overview of agricultural activities, detailing the percentage of sample involvement, hours spent, specific tasks, and challenges faced. In the sample population, 30% are engaged in planting and harvesting activities. Of these, 7% spend less than 4 hours on these tasks, 32% focus on planting, harvesting, and livestock care, and 35% face challenges such as limited access to resources and adverse weather conditions. Livestock care and agro-processing involve 20% of the sample, with 17% dedicating 4-6 hours, 26% engaged in tasks like livestock care, milking, and cheese-making, and 15% encountering issues related to limited market access and seasonal fluctuations. Another 20% of the sample are involved in agro-processing and eco-tourism, with the majority (39%) spending 6-8 hours on these activities. Only 12% are engaged in agro-processing and tour guiding, while 10% face land ownership issues and marketing challenges.

Additionally, 20% of the sample participate in planting and harvesting, with 21% dedicating 8-10 hours to these activities. Within this group, 10% focus on planting, harvesting, and pest control, and 23% struggle with limited access to technology and water scarcity. Finally, 10% of the sample is involved in gardening and livestock care, with 16% spending more than 10 hours on these tasks. In this category, 20% are engaged in gardening and feeding livestock, while 17% face physical limitations and weather dependency. Overall, the distribution of time and tasks highlights a varied engagement in agricultural activities, with significant challenges related to resource access, market conditions, and environmental factors impacting the effectiveness and efficiency of these activities.

|

Figure 3. Household responsibilities of women (Study area) |

Source: Field survey of sample area.

The survey data reveals various insights into household responsibilities and the challenges of balancing them with agricultural duties. Cooking, cleaning, and childcare are the primary household tasks for 63% of the sample, while 11% focus on household finances and grocery shopping, and 2% on gardening and home repairs. Additionally, 17% manage cooking, cleaning, and gardening, while 7% handle household chores and elder care.

In terms of balancing agricultural and household duties, 23% of respondents find it manageable but sometimes challenging, 10% struggle occasionally but find it manageable, 9% set priorities despite struggles, 15% manage well with planning, and 45% have adjusted their routines to make time for hobbies. When it comes to challenges in managing household duties, 37% cite time management and household finances as major issues, 22% face difficulties with household chores and childcare, 23% are constrained by time and caring for aging parents, and 9% each face limited access to education and challenges related to aging infrastructure and healthcare.

|

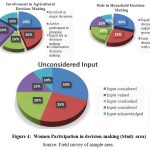

Figure 4: Women Participation in decision-making (Study area). |

Source: Field survey of sample area.

The data on decision-making involvement in agricultural and household contexts provides valuable insights into participation levels and the appreciation of individual contributions. In agriculture, 25% of people are involved in major decisions, and another 25% participate in collaborative decision-making, showing a mix of independent and teamwork approaches. Additionally, 20% actively engage in planning, while 15% have an equal say, reflecting diverse levels of involvement and influence. However, 15% are only consulted for major decisions, indicating areas where greater inclusion is needed. In household contexts, 30% share equal decision-making with their spouse, and 25% make joint decisions, highlighting the importance of partnership. Conversely, 20% are sole decision-makers, which can simplify processes but may place a heavy burden on one person. Another 15% have an equal say with family members, and 10% are consulted for major decisions, showing varying degrees of influence within the family.

The perceived value of input also varies, with 30% feeling their input is considered and 25% believing it is valued, suggesting that most individuals feel their contributions are significant. However, 20% feel their input is overlooked, and 10% feel it is merely acknowledged, indicating potential dissatisfaction and disengagement. These findings emphasize the need for more inclusive and participatory decision-making processes in both agriculture and households. Ensuring that everyone’s input is heard and valued can enhance engagement, satisfaction, and overall effectiveness in managing agricultural activities and household affairs. Policymakers and community leaders should work towards creating environments that encourage equal and joint decision-making, empowering all individuals to contribute meaningfully.

|

Figure 5: Women’s Approach to Agricultural tourism (Study area). |

Source: Field survey of sample area.

Challenges and Opportunities

Women in agriculture and household management face multifaceted challenges that hinder their full participation and success in these domains.

Challenges

Access to training and resources: Limited access to training programs and agricultural resources poses a significant challenge for women in rural areas. Without adequate training, women may struggle to adopt modern agricultural practices, leading to decreased productivity and profitability. Gender stereotypes: Gender stereotypes deeply ingrained in society frequently limit women’s involvement in decision-making processes and leadership positions within the agricultural sector. These stereotypes perpetuate the notion that farming is primarily a man’s domain, undermining women’s contributions and hindering their empowerment. Limited access to markets and financial resources: Women farmers often face challenges in accessing markets to sell their produce at fair prices. Additionally, limited access to financial resources and credit further impedes their ability to invest in their farms, purchase necessary inputs, and expand their agricultural activities. Household responsibilities: Balancing household responsibilities, such as childcare and household chores, with agricultural work can be daunting for women. The dual burden of work often leads to time constraints and limited opportunities for women to fully engage in agricultural activities.

Opportunities

Empowerment through education and training: Providing women with access to education and training programs in agricultural practices can empower them with the knowledge and skills needed to enhance productivity and profitability on their farms.

Gender-inclusive policies: Implementing gender-inclusive policies which promotes women’s involvement in decision-making procedures and offer alike access to resources and opportunities can help break down gender barriers in the agricultural sector. Financial services and markets Assessment: Enhancing market access and financial service utilization for women, particularly credit and savings mechanisms, can enable them to invest in their farms, expand their businesses, and access new market opportunities. Support networks and capacity building: Establishing support networks and capacity-building programs for women farmers can provide them with the necessary resources, mentorship, and information to overcome challenges and seize opportunities in the agricultural sector. Technology adoption: Embracing technological innovations and digital tools can help women farmers improve efficiency, access market information, and connect with buyers, thereby enhancing their competitiveness and market reach.

Discussion

The presented findings offer a critical lens into the intricate interplay of gender, education, socio-economic status, and cultural context in shaping women’s roles and perspectives within the realms of tourism and agriculture in rural settings. This study contributes significantly to the existing body of knowledge by illuminating the nuanced factors influencing women’s attitudes towards development initiatives. The study’s core argument is that women’s participation in and attitudes towards tourism and agricultural development are profoundly influenced by a complex web of intersecting factors. Education emerges as a pivotal determinant, shaping women’s awareness of potential benefits and their capacity to engage in decision-making processes. Socio-economic status, particularly as reflected in spousal occupation, further stratifies women’s perspectives, with those from more affluent backgrounds exhibiting greater support for tourism. The dual burden of agricultural and domestic responsibilities significantly constrains women’s time and energy, limiting their ability to participate fully in economic activities. Moreover, the study underscores the persistent influence of gender stereotypes and norms, which hinder women’s involvement in agricultural decision-making.

To deepen the analytical rigor, the study could benefit from grounding its findings within established theoretical frameworks. Feminist theory could provide a robust lens to examine the gendered power dynamics shaping women’s experiences. Intersectionality theory would allow for a nuanced exploration of how multiple social identities (gender, class, education) intersect to create unique experiences of disadvantage or privilege. Social capital theory could be employed to analyse the role of social networks and relationships in influencing women’s attitudes and behaviors.

The study’s findings have significant implications for policymakers, development practitioners, and researchers. To effectively empower women and promote gender equality in rural areas, it is imperative to address the identified challenges through targeted interventions. These may include:

Expanding educational opportunities for women to enhance their awareness and capacity to participate in development initiatives.

Implementing gender-sensitive policies that challenge traditional gender roles and norms.

Providing access to financial resources and support services to enable women to overcome economic constraints.

Strengthening women’s participation in decision-making processes at the household, community, and policy levels.

Promoting diversified livelihood opportunities that integrate agriculture and tourism in a sustainable manner.

While the study makes valuable contributions, it also highlights areas for further research. Future studies could explore the long-term impacts of tourism on women’s lives, the role of technology in empowering rural women, and the effectiveness of different interventions in promoting gender equality in the context of tourism and agriculture. By illuminating the complex factors shaping women’s perspectives on tourism and agricultural development, this study provides a foundation for designing effective interventions to empower rural women. It underscores the need for a holistic approach that addresses both structural and individual-level barriers to women’s participation in economic activities.

Conclusion

The study’s data provide a comprehensive analysis of women’s roles in agricultural and household activities, their participation in decision-making, and their approach to agricultural tourism in Sikkim. Demographically, the sample consists mainly of youthful and married women, with a diverse range of educational backgrounds. Farming emerges as the primary occupation, reflecting the agrarian nature of the economy, while a significant entrepreneurial presence indicates growing economic diversification. The balance of agricultural and household responsibilities reveals that many women face substantial challenges in time management and resource access, highlighting the need for targeted support to improve their efficiency and well-being. These findings align with Hypothesis 1, which posits a significant relationship between women’s age and their involvement in agricultural activities, as well as Hypothesis 2, suggesting that more hours spent on agricultural tasks correlate with greater challenges in balancing household duties.

Participation in decision-making shows a mix of collaborative and individual roles, with a significant portion of women feeling their contributions are valued, though some report their input is overlooked. This supports Hypothesis 3, indicating that women’s education level influences their participation in decision-making processes. The interest in and perception of agricultural tourism among women suggest strong potential for economic growth and community development, corroborating Hypothesis 4, which links awareness and positive perceptions of agricultural tourism to a higher interest in participation. The study also highlights the main challenges women face, such as limited market access and resource constraints, and the opportunities available, like training programs and marketing platforms. These findings support Hypothesis 5, suggesting that women who view agricultural tourism as beneficial are more likely to engage in it. Overall, the data underscore the transformative potential of integrating women’s empowerment with sustainable agricultural practices and tourism, promoting holistic rural development in Sikkim.

In conclusion, organic farming and agro-tourism hold immense promise for fostering sustainable rural development and empowering women in Sikkim. By leveraging the socio-economic benefits of organic agriculture and promoting inclusive agro-tourism initiatives, policymakers and stakeholders can unlock new opportunities for economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability in the region. However, concerted efforts are required to address challenges and create an enabling environment for the continued success of these initiatives.

Acknowledgment

The author is thankful to Concerned Ward / Area Counsellors and Panchayats as well as Area MLAs, for allowing and kind support to let me carry out the field survey in their respective jurisdictions, which was an important part for ensuring the data necessary for this research work. I also give my heartfelt thanks to the respondents who participated in this study. Their willingness to spend time and give thoughtful responses helped my study to be a success.

Funding Sources

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Tourism Department, Self Help Group, Primary Field Survey.

Ethics Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal, subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

This research did not involve human participants, animal, subjects, or any material that requires ethical approval

Author’s Contribution

Conceptualization, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review and editing, A.C. Author have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Daw ME. Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security in an Era of Oil Scarcity: Lessons from Cuba. Experimental Agriculture. 2009;45(3):378-379. doi:10.1017/S0014479709007741. 7th June 2024.

CrossRef - Kumar., M. Pradhan., N. Singh. Sustainable Organic Farming in Sikkim: An Inclusive Perspective. In: SenGupta, S., Zobaa, A., Sherpa, K., Bhoi, A. Advances in Smart Grid and Renewable Energy. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering: 435. Singapore: Springer; 2018: 367-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4286-7_36.4th Aug 2024

CrossRef - Sikkim Organic Certification. Agriculture and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA). Annual Report; 2017.11th June 2024

- Orhan O., Akcaoz H. Rural women, and agricultural extension in Turkey. Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment.2010;8 (1) : 261-267. 16th June 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 267381987_ Rural_women_and_agricultural_extension_in_Turkey ., January 2010. 1st Aug 2024

- Anriquez, Stamoulis K. Rural Development and Poverty Reduction: Is Agriculture Still the Key? The Electronic Journal of Agricultural and Development Economics.2007;4(1): 5-46.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5021691_Rural_Development_and_Poverty_Reduction_Is_Agriculture_Still_the_Key. 2007/02/01. 29th July 2024. - Kruja D., Lufi M., Kruja I. The role of tourism in developing countries. The case of Albania. European Scientific Journal.2022; 8(19):129-141. ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print)

- Streifeneder T., Thomas D. Agritourism in Europe: Enabling Factors and Current Developments of Sustainable On-Farm Tourism in Rural Areas. In: Devkant K., Satish Chandra B. Global Opportunities and Challenges for Rural and Mountain Tourism. United States, Pennsylvania: GI Global; 2020. 40-58. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-1302-6.ch003

CrossRef - Gao S., Huang S., Huang Y. Rural tourism development in China. International Journal of Tourism Research. 2009;11(5):439-450. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.712. 2nd Aug 2024.

CrossRef - Hall D., Mitchell M. Rural Tourism Business as Sustained and Sustainable Development. In: Hall D., Mitchell M., Kirkpatrick I. Rural Tourism and Sustainable Business. Bristol, Blue Ridge Summit: Channel View Publications; 2005:353-364. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781845410131-022. 4th June 2024.

CrossRef - Taleska M. Agrotourism as an opportunity for revitalization of rural areas. V congress of the geographers from Republic of Macedonia. 26/09/2015. MGD, Skopje. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311924444_AGROTOURISM_AS_AN_OPORTUNITY_FOR_REVITALIZATION_OF_RURAL_AREAS. 3rd June 2024.

- Songul A., Mustafa Kader A., Fatma Ocal K., Tecer A. The potential of rural tourism in turkey: the case study of Cayonu. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research. 2015: 52(3):853-859. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285611750_The_potential_of_rural_tourism_in_Turkey_The_case_study_of_Cayonu. September 2015. 10TH June 2024.

- Krishna D K., Sahoo A K. Origin and Status of Agritourism in India: A Detailed Comprehension. Agriculture and Food: E-Newsletter. 2020: 2(8): 67-70. https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/376088845_Origin_and_Status_of_Agritourism_in_India_A_Detailed_Comprehension. August 2020. 3rd July 2024.

- Agri-Tourism World. Accessed July 12, 2024. https://agritourismworld.com/

- Chhetri A. Organic agro tourism of Sikkim: An initiative for sustainable rural development, women empowerment, and green environmental practices. Khoj: An International Peer Reviewed Journal of Geography;2020 ;7(1); 67- 73, Article DOI: 5958/2455-6963.2020.00007.7

CrossRef - Departments/food-security-and-agriculture-development-department Government of Sikkim, India.

- Rogerson, P. Statistical Methods for Geography. India: SAGE Publications;

CrossRef