Introduction

Krishi Vigyan Kendra (Farm Science Centre) an innovative science–based institution, plays an important role in bringing the research scientists face to face with farmers. The main aim of Krishi Vigyan Kendra is to reduce the time lag between generation of technology at the research institution and its transfer to the farmers for increasing productivity and income from the agriculture and allied sectors on sustained basis. KVKs are grass root level organizations meant for application of technology through assessment, refinement and demonstration of proven technologies under different ‘micro farming’ situations in a district (Das, 2007). Front line demonstration (FLD) is a long term educational activity conducted in a systematic manner in farmers fields to worth of a new practice/technology. Farmers in India are still producing crops based on the knowledge transmitted to them by their forefathers leading to a grossly unscientific agronomic, nutrient management and pest management practices. As a result of these, they often fail to achieve the desired potential yield of various crops and new varieties. Potential yield is determined by solar radiation, temperature, photoperiod, atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and genotype characteristics assuming water, nutrients, pests, and diseases are not limiting the crop growth. Under rainfed situation, where the water supply for crop production is not fully under the control of the grower, water-limiting yield may be considered as the maximum attainable yield for yield gap analysis assuming other factors are not limiting crop production. However, there may be season-to-season variability in potential yield caused by weather variability, particularly rainfall. Water-limiting potential yield for a site could be determined by growing crops without any growth constraints, except water availability (Singh et al., 2001).The baseline survey was conducted by Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Dungarpur during 2006-07 under National Agricultural Innovation Project entitled “Livelihood and Nutritional Security of Tribal Dominated Area Through Integrated Farming System and Technology Models” and the aim of project was to research a replicable model for sustainable rural livelihood security. In the project, a bouquet of 25 technologies were tested in Faloj cluster consisting of 5 villages and involving 1142 households in Faloj, Dhani, Ghatau, Dabela and Futi talai villages. It was found that farmers were using old varieties of vegetable crops without proper use of recommended scientific package of practices. Keeping in view the constraints, Krishi Vigyan Kendra Dungarpur conducted front line demonstrations on major vegetable crops which would ensure livelihood, nutritional security and economic empowerment of tribal households at faster pace.

Materials and Methods

Profile of the Study Area

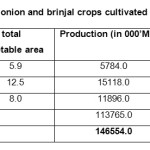

Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Dungarpur (situated at 23.83°N latitude, 73.72°E longitude and an altitude of 579.5 m above msl) belonging to Humid Southern Plain of Rajasthan (Agro climatic Zone IV b). In the Eastern and Northern borders of Banswara and Udaipur districts, respectively while it adjoins the State of Gujarat in Southern and Western part. Dungarpur district is the smallest district of the state covering an area of 385592 hectares only, which is 1.13 percent of the total area of Rajasthan. Average land holding is 0.67 hectare per capita, which is lowest in the state. Most parts of the district are covered by hills. Agriculture is the main source of the livelihood in the Dungarpur district of Rajasthan with a gross cropped area of 131517 hectare (Govt. of Rajasthan, 2010-11). The district has a semi-humid climate with average temperature of the district varies from 21.8-460C in summer and 11-260C in winter and annual rainfall is about 729mm. Dungarpur is one of the most backward districts of Rajasthan (India) having 70.8 % of populations are tribal (Population Census, 2011). There are three major vegetable crops being cultivated in Dungarpur which includes okra, onion and brinjal. Table 1 shows the area, total production and productivity of okra, onion and brinjal vegetable crops cultivated in the India during 2010-11 (Indian Horticulture Database, 2011). It is evident that 26.4 per cent of the total vegetables cultivated area has been covered under okra, onion and brinjal in India. The 12.5 area of total vegetables comes under onion crop and per cent of total vegetable production 10.3 is covered by onion crop. In Rajasthan, the total area under vegetable production is 143.92 thousand hectares with the production of 620.11 thousand metric tons (Govt. of Rajasthan, 2010-11). The present investigation was carried out in the adopted villages located in the operational area of Krishi Vigyan Kendra Dungarpur with the objective to identify the yield gaps as well as to work out the difference in input cost and monetary returns under front line demonstrations and farmers’ practices (local checks) of okra, onion and brinjal vegetable crops. Soil of the study area is sandy loam in texture with alkaline in reaction (pH 8.3), low organic carbon (0.47 g kg-1 soil), low nitrogen (247 kg ha-1), medium phosphorus (18.7 kg ha-1) and high in available potassium (267 kg ha-1). The critical inputs were applied as per the scientific package of practices recommended by the research wing of Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur (Anonymous, 2007). The data on production cost and monetary returns was collected for five years (2007-08 to 2011-12) from front line demonstration plots to workout the economic feasibility of improved and scientific cultivation of vegetables. Besides, the data from local checks, data were also collected where farmers were using their own practices for cultivation of vegetable crops. The technology gaps, extension gaps and technology index were calculated as given by Samui et al., (2000) as:

1. Technology gap = Potential yield – Demonstration yield

2. Extension gap = Demonstration yield – Yield from farmers practice (Local check)

![]()

Results and Discussion

Description of Front Line Demonstrations

The details of demonstrations conducted by Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Dungarpur are presented in Table 2. In each front line demonstration, the improved variety suitable to local condition was selected and the recommended package of practices was adopted. Some of the major differences between the improved technologies adopted in front line demonstrations and farmers practices (local checks) adopted by farmers in different vegetable crops are summarized as below.

Okra

The improved technologies included improved hybrid varieties (cv. Bhindi No. 10 and Cylinder), nutrient management (120:60:50 NPK kgha-1) and pest management (Dimethoate 30EC @1.2lha-1 or Cunfidor 200SS @1.0lha-1 and Malathion 35EC @ 1.2lha-1) were tested under demonstrations. Crop was sown by using seed @ 20 kg ha-1 with crop geometry 30×15cm. The whole of Phosphorus and Potash in the form of Diammonium Phosphate (DAP) and Murat of Potash (MOP) were applied as basal dose and Nitrogen in the form of Urea was top dressed in two equal splits at 30 and 60 days after sowing. The herbicide, Basalin (fluclorolin 45%EC) @ 1.6lha-1 was applied at pre sowing of okra crop. The Dimethoate 30EC @1.2lha-1 or Cunfidor 200SS @1.0lha-1 was applied at the time of incidence of yellow mosaic virus and Malathion 35EC@ 1.2lha-1 was applied for the control of fruit borer.

Onion

Farmers were using local variety of onion. The seed rate used by the farmers was very high (12-15 kgha-1). Chemical fertilizers i.e. Urea and DAP were used by the farmers. In improved technologies includes improved varieties (cv.N 53 and AFDR and seeds was treated with Thiram @ 2.5g kg-1seed), nutrient management (50:50:70 NPK kgha-1) and weed management (Pendamethalin 30%EC @3.0lha-1 pre transplanting) were tested. The seeds of onion were sown in the raise bed nursery. The size of 15-20cm height, 45cm width and length as needed raise bed nursery were prepared, the seeds were sown in 5-7cm row distance and 1-2cm deep. After sowing of seeds in the raise bed, watering was done by water cane or sprinkler. The seed were sown between 3rd week of October to 1st week of November. After 35-40 days, single seedling per hill was transplanted from nursery to field with crop geometry of 15×10 cm. The whole of the Phosphorus and Potash were applied in the form of Diammonium Phosphate and Murat of Potash as basal dose and Nitrogen in the form of Urea was top dressed in two equal splits at 30 and 45 days after transplanting. For the control of weeds, Pendamethalin 30% EC @3.0lha-1 was applied before transplanting of the crop. Dithane M 45 @1.0lha-1 was use for the control of purple blotch in onion (Alternaria porri).

Brinjal

In case of brinjal (Table 2), farmers were using local or improved varieties of brinjal. The farmers were sowing the seeds in flat bed using broadcast method without the use of any herbicides. In improved technologies, included hybrid variety (Ravaiya), nutrient management (90:60:50 NPK kgha-1) and weed management (Fluclorolin 45%EC @1.6lha-1 at pre transplanting) were tested. Brinjal crop was sown between Ist week to 3rd week of November by using seed @ 400g ha-1.The seeds of brinjal were sown in the raise bed nursery. The size of 15-20cm height, 45cm width and length as needed raise bed nursery were prepared, the seeds were sown in 5-7cm row distance and 1-2cm deep. After sowing of seeds in the raise bed, watering was done by water cane or sprinkler. After 30-35 days, seedling of brinjal were transplanted in the field with crop geometry of 70×60cm. Whole of the Phosphorus and Potash were applied in the form of DAP and MOP as basal dose and Nitrogen in the form of Urea was top dressed in two equal splits at 25 and 45 days after transplanting of crop. For the control of weeds, Basalin (fluclorolin) @1.6lha-1 was applied before transplanting of the crop. At the incidence of shoot borer (Leucinodes orbonalis), Profenophos @1.2lha-1 was applied.

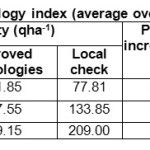

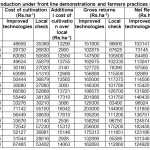

Economic Impact of Front Line Demonstrations

During the period of study, it was observed that in front line demonstrations of improved technologies increased productivity of all the vegetables over respective local checks (Table 3). The improved technologies recorded higher productivity of brinjal and onion 299.15q ha-1, 207.55q ha-1 as compared to farmers practices (local checks) 209.00q ha-1, 133.85q ha-1, respectively. The increase in productivity of brinjal and onion over respective local checks were 43.13 % and 55.06 %. The higher productivity of brinjal and onion under improved technologies were due to the sowing of latest high yielding varieties and adoption of improved nutrient and pest management techniques. Similar results have been reported earlier by Haque (2000), Hiremath and Nagaraju (2009) and Dhaka et al., (2010). The year wise fluctuation in yields was observed mainly on the account of variations in soil fertility status and moisture availability due to untimely rainfall every year (Table 4). Similarly, okra recorded higher productivity of 121.85qha-1 in improved technologies as compared to local check (77.81q ha-1). The increase in the productivity of okra over local check was 56.60 %. The yield improvement in okra might be due to combined effect of high yielding, moderate disease resistant hybrid varieties and adoption of improved weed and nutritional management. Similar yield enhancement in different crops in front line demonstration has amply been documented by Haque (2000), Tiwari et al., (2003), Mishra et al., (2009) and Kumar et al., (2010). Yield of the front line demonstration trials and potential yield of the crop was compared to estimate the yield gaps which were further categorized into technology and extension gaps (Hiremath and Nagaraju, 2009). The technology gap shows the gap in the demonstration yield over potential yield and it was highest in brinjal (50.85q ha-1) in comparison to onion (42.45q ha-1) and okra (28.15q ha-1). The observed technology gap was mainly attributed to rainfed conditions prevailing in the district. The other reasons include dissimilarity in soil fertility status, marginal land holdings and hilly terrain. Further the higher extension gap of 90.15q ha-1 was recorded in brinjal after onion (73.70q ha-1) and okra (44.04q ha-1). This emphasized the need to educate the farmers through various extension means for the adoption of scientific practices in cultivation of all the vegetable crops. Mukharjee (2003) has also opined that depending on identification and use of farming situation, specific interventions may have greater implications in enhancing system productivity. The data presented in Table 3 revealed that, the technology index was minimum for brinjal (14.53%) compared to onion (16.98%) and okra (18.77%). Technology index shows the feasibility of evolved technology at the farmer’s field and lower the value of technology index more is the feasibility of the technology (Jeengar et al., 2006). The inputs and outputs prices of commodities prevailed during each year of demonstrations were taken for calculating cost of cultivation, net return and benefit cost ratio (Table 4). The economic analysis of the data over five years revealed that okra under front line demonstrations recorded higher gross returns (Rs. 175313 ha-1), brinjal recorded higher net return (Rs. 124928 ha-1) and onion recorded height B:C. ratio (4.20) as compared to their local checks of respective vegetable crops where farmers got gross returns, net returns and B:C ratio of Rs. 111851ha-1, Rs. 80558 ha-1 and 2.99, respectively. Okra also recorded higher gross returns of Rs. 175313ha-1 and additional net return of Rs. 48316 ha-1 in improved technologies as compared to the improved technologies in onion and brinjal vegetable crops. The onion crop recorded highest B:C ratio of 4.20 as compared to its local check and okra, brinjal improved technologies and their local checks. The highest net returns of Rs. 124928 ha-1 was recorded under improved technologies of brinjal crop as compared to all the improved technologies of vegetable crop and their local checks. These are in corroboration with the finding of Mishra et al., (2009), Tomar (2010) and Mokidue et al., (2011).

|

Table 1: Area, production and productivity of okra, onion and brinjal crops cultivated in the India (2010-11). Click here to View table |

|

Table 2: Particulars showing the details of vegetables growing under front line demonstrations and farmers practices. Click here to View table |

|

Table 3: Productivity of vegetables, yield gaps and technology index (average over years). Click here to View table |

|

Table 4: Economics of vegetables production under front line demonstrations and farmers practices (local checks). Click here to View table |

Conclusions

Thus, the cultivation of vegetable crops with improved technologies including suitable varieties, weed management, nutrients and pest management has been found more productive and fruit yield in okra, onion and brinjal was increased up to 56.60, 55.06, and 43.13 per cent, respectively. Technological and extension gaps existed which can be bridged by popularizing package of practices with emphasis on the seed of improved vegetable hybrid varieties, use of proper seed rate, balanced nutrient application and proper use of plant protection measures. Replacement of local varieties with the released hybrid varieties of okra, onion and brinjal would increase the production and net income of these vegetable crops.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Professor and Director, Directorate of Extension Education, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, Rajasthan for providing research facilities. We are also grateful to World Bank and Indian Council of Agricultural Research for providing financial assistance.

References

- Anonymous., Package of Practices for Vegetable Crops. Directorate of Extension Education, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur. pp. 1-75 (2007).

- Das, P., Proceedings of the Meeting of DDG (AE), ICAR, with Officials of State Departments, ICAR Institutes and Agricultural Universities, NRC Mithun, Jharmapani; Zonal Coordinating Unit, Zone-III, Barapani, Meghalaya, India. Quoted by V. Venkatasubramanian, Sanjeev M. V. and A. K. Singha in Concepts, Approaches and Methodologies for Technology Application and Transfer- a resource book for KVKs IInd Edition. pp.6 (2007).

- Dhaka, B. L., Meena, B. S. and Suwalka, R. L., Popularization of Improved Maize Production Technology through Frontline Demonstrations in South-eastern Rajasthan. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 1. (1).pp.39-42 (2010).

- Govt. of Rajasthan, Agricultural Statistics Rajasthan. Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Rajasthan, Jaipur. pp. 37-42 (2010-2011).

- Haque, M. S., Impact of compact block demonstration on increase in productivity of rice. Maharashtra. Journal of Extension Education, 19. (1). Pp. 22-27 (2000).

- Hiremath, S. M, and Nagaraju, M. V., Evaluation of front line demonstration trials on onion in Haveri district of Karnataka. Karnataka Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 22. (5).pp.1092-1093 (2009).

- Indian Horticulture Database, Indian Horticulture Database, National Horticulture board, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India 85, Institutional Area, Sector – 18, Gurgaon – 122 015. pp. 1-278 (2011).

- Jeengar, K. L., Panwar, P. and Pareek, O. P., Front line demonstration on maize in bhilwara District of Rajasthan. Current. Agriculture, 30. (1-2). pp. 115-116 (2006).

- Kumar, A., Kumar, R., Yadav, V. P. S. and Kumar, R., Impact assessment of Frontline Demonstrations of Bajra in Haryana State. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 10. (1). pp. 105-108 (2010).

- Mishra, D. K., Paliwal, D. K., Tailor, R. S. and Deshwal, A. K., Impact of Frontline Demonstrations on Yield Enhancement of Potato. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 9. (3).pp.26-28 (2009).

- Mokidue Islam, Mohanty, A. K. and Sanjay Kumar, Correlating growth, yield and adoption of urdbean technologies. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 11. (2).pp.20-24 (2011).

- Mukharjee, N., Participatory learning and action. Concept publishing company, New Delhi, India. pp.63-65 (2003).

- Population Census, Population Census of Rajasthan. Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Rajasthan, Dungarpur. pp. 1-50 (2011).

- Samui, S. K., Maitra, S., Roy, D. K., Mondal, A. K. and Saha, D., Evaluation on front line demonstration on groundnut (Arachis hypogea L). Journal of Indian Society of Coastal Agriculture Research, 18.pp.180-183 (2000).

- Singh, P., Vijaya, D., Chinh, N. T., Pongkanjana, A., Prasad, K. S., Srinivas, K. and Wani, S. P., Potential Productivity and Yield Gap of Selected Crops in the Rainfed Regions of India, Thailand, and Vietnam. Natural Resource Management Program Report no. 5, 50. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, pp.1-25 (2001).

- Tiwari, R. B., Singh, V. and Parihar, P., Role of front line demonstration in transfer of gram production technology. Maharashtra Journal of Extension Education, 22. (1).p.19 (2003).

- Tomar, R. K. S., Maximization of productivity for chickpea (Cicer arietinum Linn.) through improved technologies in farmer’s fields. Indian Journal Natural Products and Resources, 1. (4). pp.515-517 (2010).